The German-born designer Peter Muller-Munk always stood in the shadow of celebrated colleagues such as Norman Bel Geddes and Raymond Loewy. But his contribution to the ‘American way of life’ was significant, as shown in a new major exhibition in Pittsburgh…

“Design is an attitude. It is not a magic mixture. It’s bread and butter, and sometimes it is also jam.” Those were Peter Muller-Munk’s words to his students at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. The Institute was the first in the world to offer a course for young industrial designers after the Second World War. It was here that the German-born immigrant enjoyed his greatest successes as a teacher and as a designer. The exhibition ‘Silver to Steel’ at the Carnegie Museum of Art sheds new light on the important designer, and looks at his innovative and internationally acclaimed everyday items from the ‘Mad Men’ era.

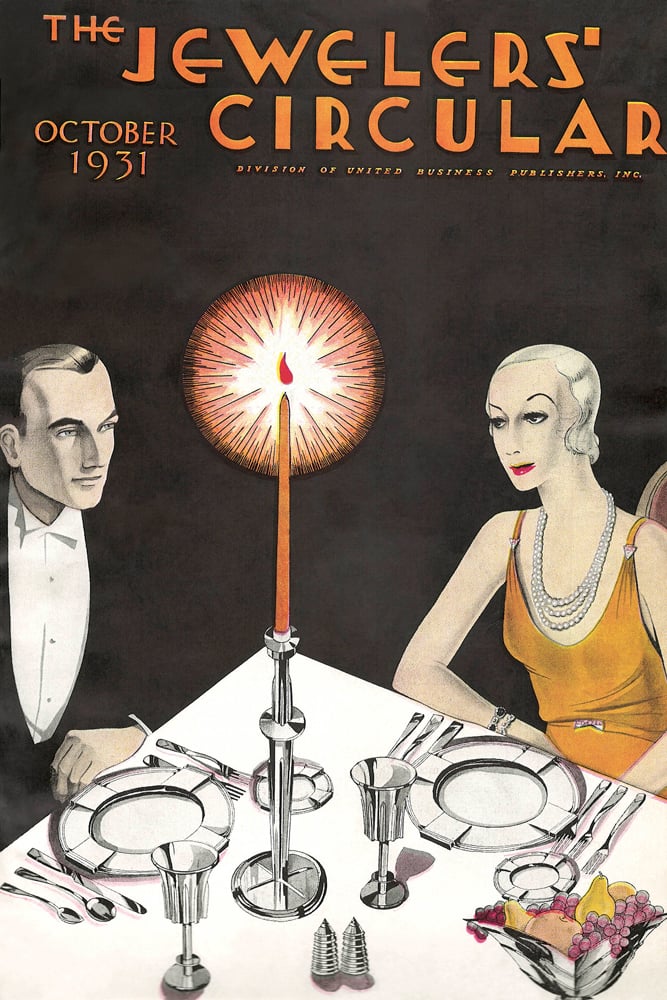

Shortly after arriving in America in 1926, Muller-Munk paid to have the umlaut removed from his name. He was an eloquent and elegant young man, who used his experience as a silversmith in the European arts and crafts movement to land a job at Tiffany & Co. Unlike in Germany, where there was little need for luxury items in the difficult economic situation following the First World War, New York’s economy was flourishing, and people quickly became aware of Muller-Munk’s talent. Within a year, he’d started his own business creating silver bowls, brush sets for ladies, shaving sets for men, and trophies for gentlemen sailors.

He skilfully combined the decorative Art Deco style with more quirky European Modernism, as demonstrated by his new home. Although Muller-Munk had been trained in traditional crafts, he became increasingly interested in the design of industrial products, and started giving lectures about being a designer. He was offered a job lecturing in the mid-1930s at the Carnegie Institute, where he was finally able to realise his ideas. “Nothing is worse than factory-built products that are made to look handmade,” he said. “It lacks the courage of aesthetic autonomy.” He would send his students into the steelworks to understand the material and its properties, as well as glass and ceramic factories. He also promoted contact between the Institute and established design and engineering companies – an approach that was unusual for the time.

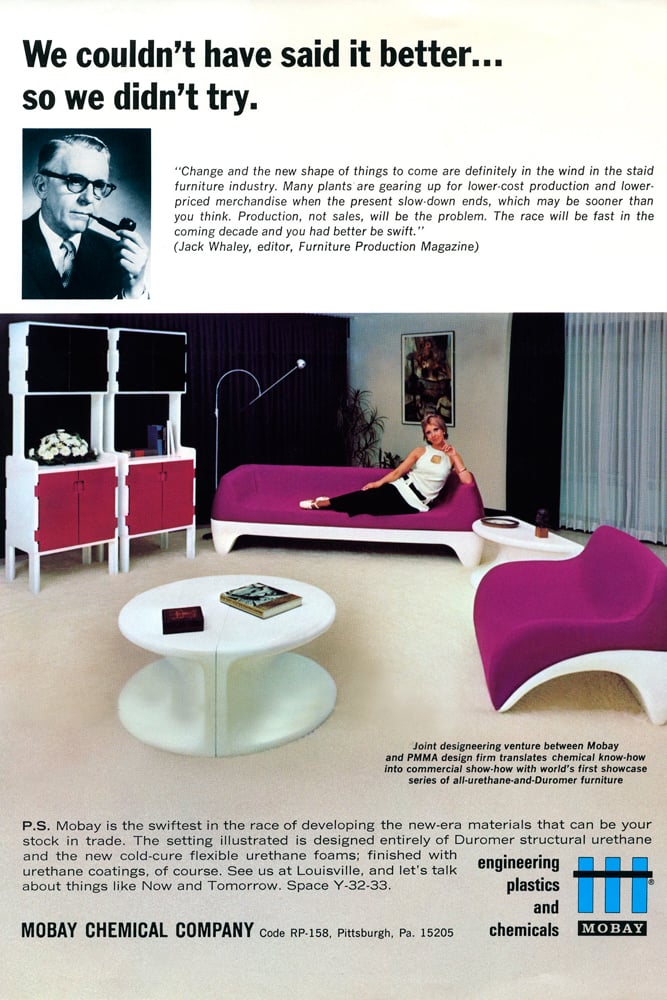

When the Second World War broke out, Muller-Munk was charged with designing camouflage material for the US armed forces; and after the War, he helped establish the ‘American way of life,’ capitalising on the growing prosperity of luxury cars, homes and everyday objects. Muller-Munk designed vast fridges, chrome trim for sailboats, a cooler for Coca-Cola, plus radios and video cameras. To cope with the demand, he established his own office – Peter Muller-Munk Associates (PMMA) – where he employed some of his ex-students. The US Government even consulted with Muller-Munk for development assistance, with regard to modernising countries such as India and Turkey.

Muller-Munk was more than a mentor, entrepreneur and skilful self-marketer. “We are the sculptors of mass production,” he once wrote. “What surrounds the modern man was designed by someone with a sense of colour, shape, material and technology, whether it’s a gasoline pump, a bath or a plastic brush.” Unlike Geddes or Loewy, Muller-Munk never worked for the US automobile industry. He worked in a more traditional way, involving himself from the very beginning of the design process. “Good design is not a luxury. For a product to prevail, you have to know its market, and then supply the best quality.” His words still ring true today, some 65 years later.

Photos: CMOA

The exhibition ‘Silver to Steel’ in the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh runs until 11 April 2016. For more information, see cmoa.org.