Artists have been fascinated by the automobile since its invention. As subjects of love, hate and even fetish, cars have found themselves in studios and galleries across the world. And more often than not, this is simply because artists themselves are self-confessed enthusiasts…

It’s not known how the curator of the Louvre reacted when Italian Filippo Tommaso Marinetti exhibited the ‘Futurist Manifesto’ in 1909, featuring a ‘roaring’ racing car, said to be ‘more beautiful than the victory at Samothrace’. Regardless, six decades later, the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely presented a Lotus Climax V8 at his museum in Basel, as a poignant reminder of the legendary Scottish driver, Jim Clark. Cars and art share an enduring relationship. For the Futurist artists, the thrill of speed was tangible.

No sooner had the car been invented than artists discovered its enormous potential. In 1898, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec produced a lithograph in his characteristic linear style named ‘The Motorist’, depicting a man at the wheel of an early automobile. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Futurist Giacomo Balla put cars (which were still very much luxury objects) at the centre of many of his pieces. The versatile colour artist Sonja Delauney not only designed hats and capes for motorists, but also painted several early Citroëns; a precursor to the later Citroën ‘Art Cars’. Tamara de Lempicka’s renowned 1929 self-portrait depicts her at the wheel of a green Bugatti and, on the subject of Bugattis, Rembrandt – founder Ettore’s younger brother – created remarkable bronze animals, some of which were used as bonnet ornaments on Ettore’s famous cars.

Following World War II, there was a triumphal surge in car culture, leaving its mark on society and the environment. The artwork of old might have languished, but the new, groundbreaking art movement quickly took up the subject of mobility – Andy Warhol’s series of photos of a car accident, for example. Roy Lichtenstein was at it, too; his ‘In the Car’ pop art piece quickly became prominent in popular culture.

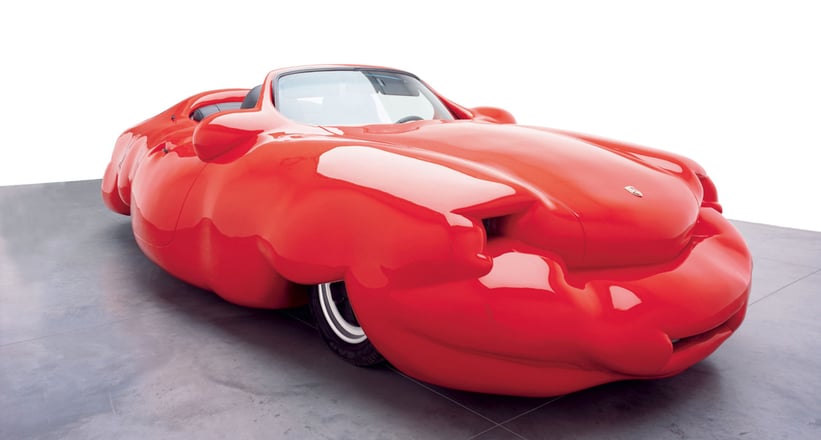

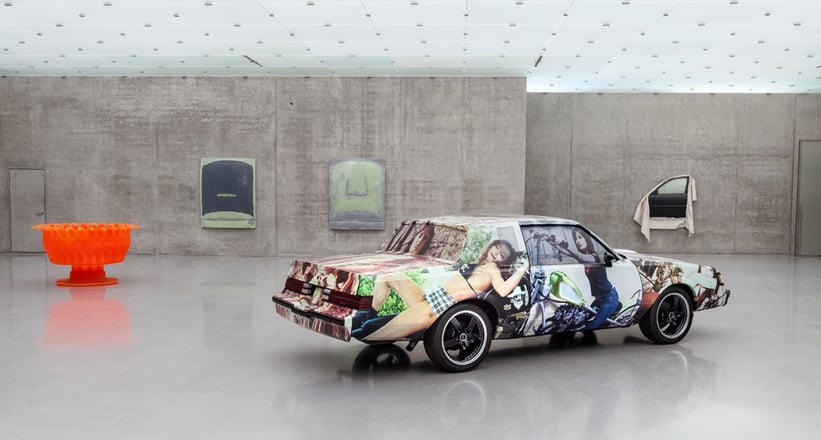

The car as sculpture grew increasingly popular, too. Artists such as César saw poetry in their proportions, interpreting cars in deformed ways. The early 1970s saw US artist Chip Lord create ‘Cadillac Ranch’, a series of tailfin saloons seemingly half buried in the ground, built as a symbol of the brand’s evolution. Frenchman Arman presented ‘Traction Avant, après traction’, essentially a rusted carcass of the car presented as though it had just been unearthed. Wolf Vostell’s Cadillac in concrete in Berlin symbolised modern worship of the automobile, Erwin Wurm’s ‘Fat Car’ was a Porsche on some serious steroids and Dutch artist Madeleine Berkhemer’s Maserati and Lamborghini installations document her penchant for nylon stockings.

Now iconic, BMW’s Art Cars only came to be thanks to former racing driver Hervé Poulain, and his realisation that the forms and surfaces of racing cars were the ideal platform for artists to document their work.

Marinetti recognised that racers and artists have much in common – they both understand the beauty in speed, and the idea of sudden death, for example. Take the positive relationship between Tinguely and Swiss driver Jo Siffert, the latter who tragically died doing what he loved. For his deceased friend, Tinguely dedicated a striking fountain in his and Siffert’s hometown of Fribourg. It still stands today, and is well worth a visit if you’re ever in the area…

Photos: Getty Images / Rex Features / Museum Tinguely / BMW / Bugatti